What Stones Were Used To Repair Broad Wall Nehemiah

The biblical books Nehemiah 2 and 3 relay the story of Nehemiah'southward trip effectually the destroyed town of Jerusalem and of the rebuilding of its fortifications. Despite the detailed description of walls and gates, scholars debate the actual size of the settlement in Persian times and fifty-fifty question whether the walls were actually reconstructed. This paper investigates the facts `on the ground'. Was any town wall of the Persian menstruation ever excavated? How large was Nehemiah'southward Jerusalem and how did it function within the Persian empire? Was it a walled town with a central temple, the seat of the governor, a heart of administration, religion and economic system? Or was it a small undefended settlement in which only the local temple had whatever significance? Spoiler alarm: there are as many opinions as there are scholars, and the archaeological evidence is meagre.

By Margreet L. Steiner

Independent Archeologist

October 2022

Nehemiah

Nehemiah 2:11-15 recounts how the prophet arrives in Jerusalem and immediately sets out in the night with some of his men to inspect the town walls. He leaves the settlement through the Valley Gate and and then rides on his donkey in the direction of the Jackal Well and Dung Gate. The trip continues to the Fountain Gate and the King's Pool. Eventually he returns through the Valley Gate. What he encounters is terrifying. The walls are demolished, the gates reduced to ashes. In some places it is impossible to go along because of the corporeality of debris on the gradient. Nehemiah decides that the fortifications have to exist rebuilt.

Nehemiah 3 is even more specific. Families and professional person groups take on the responsibility for repairing stretches of the wall, while gates are provided with attics, doors, bolts and bars, and towers are rebuilt. The high priest Eliashib, for case, rebuilds the Sheep Gate together with his swain priests, while the sons of Hassenaah tackle the Fish Gate.

No other biblical text is as explicit near the walls of Jerusalem as Nehemiah 3. Not but 9 gates are mentioned, but too other characteristic parts of the town such as the Tower of the Hundred and the Tower of Hanael, the Broad Wall, the Puddle of Siloam, the King's Garden, the steps going down from the City of David, the tombs of David, the artificial pool, the House of the Heroes and many more.

What a wealth of data on the lay-out of Jerusalem in Persian times! Since the project involved the reparation of older constructions, this text gives information near the boondocks at the end of the Iron Age, just before its destruction by the Babylonians in 586 BC, equally well.

Many biblical scholars have been allured by these texts to sketch a map of the city based on the descriptions therein - run into for example https://medium.com/@chrisvonada/the-courage-and-calling-of-nehemiah-1b64df490373 . In this map the walls environment the southeastern hill and the Temple Mount but; information technology is assumed that other parts of the Late Iron Historic period city were non reconstructed.

Unfortunately, the Bible texts remain vague on the verbal location of these structures. That the order of the buildings in the text is the same as the club `on the footing' is likely just not certain. Some other problem: if this list includes only the walls effectually the southeastern hill and the Temple Mount, then nine urban center gates seem to be an caricature for such a minor surface area. Perhaps it rather encompasses all the destroyed city gates of Jerusalem, including those around the western hill. But is it plausible that these were repaired too by the modest group of people who lived in the city after the Exile? These texts have clearly been written for people who lived in Jerusalem and knew exactly where the constructions mentioned were located, not for later generations not acquainted with the town. These ambiguities renders the reconstructions uncertain, and with it our view of Jerusalem in the Persian catamenia.

Archeologist have non been silent either. A whole series of publications on Jerusalem in the Persian catamenia has seen the light of day. Contempo ones include Finkelstein 2008, Lipschits 2009, Ristau 2022, and Ussishkin 2006. However, it is not easy to notice out what exactly has been excavated and how biblical texts and archaeological finds relate to each other. Very little fabric has been unearthed from Western farsi times, and what has been establish is difficult to appointment with precision. Due to this dearth of material, interpretations are becoming increasingly of import. And those interpretations tin be quite diverse.

The oldest settlement of Jerusalem was not located in what is now called the Former City, but on the hill southeast of it. This hill is now ordinarily referred to every bit the City of David, but that is a fairly recent name (Steiner 2022).

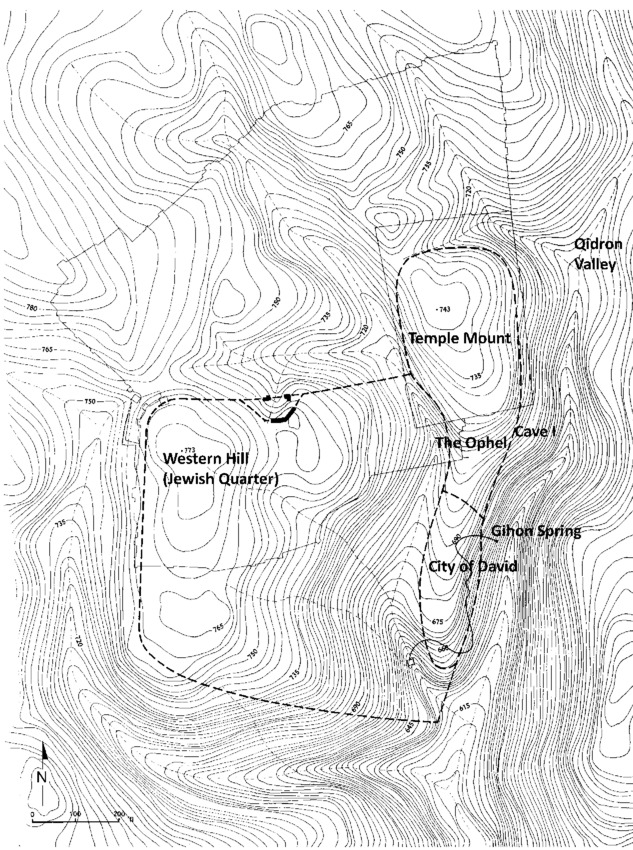

Programme of Jerusalem in the Iron Age. (Courtesy Ancient Jerusalem Projection).

Only since the cease of the 19th century do we know that the boondocks from the Bronze and Fe Ages, roughly the menstruum from 3200 - 600 BC, was built well-nigh the only natural leap in the area, the Gichon spring at the foot of the eastern slope of the southeastern hill (Steiner 2022). At the pinnacle of that hill and on its eastern and western slopes the remains of biblical Jerusalem have been constitute. It was only late in the Iron Age that the settlement expanded over the western hill. This town was destroyed by the Babylonians in 586 BC, and many of its inhabitants were sent into exile. After this devastation the wider area was largely, but non entirely, abandoned. Villages still supplied grain and other products, governors were appointed, residing offset in Mizpa and later in Jerusalem, and for many people life will have taken its traditional form.

The biblical sources are largely silent on what happened in Judah and Jerusalem after the Babylonian destruction. The accent is on the exiles and on the return to the old land after the Persians had conquered Babylon in 539 BC and included Judah into their empire. The Persian kings allowed exiles from many countries to return to their lands, and some made utilise of that, others did not; many Judeans connected to alive in Babylonia. Whether the biblical stories faithfully stand for this return is a problem we will pass over hither. Suffice to say there is hardly any archaeological evidence of a large population growth as a result of immigration.

Archaeology and the walls of Jerusalem

Jerusalem was desolate after the devastation. Its walls were destroyed, houses had collapsed, the famous temple was robbed and set on fire, and a large part of the administrative aristocracy and craftsmen were taken into exile. In this respect, the description in Nehemiah three is right. Whoever wandered around the erstwhile metropolis walls had to climb over a mass of stone and sometimes could not continue at all; large piles of rubble blocked the manner. Information technology seems obvious that Nehemiah wanted to restore the walls to make the city habitable once more. But did he do it? Did Jerusalem get a walled settlement in Persian times, or is that an unlikely notion? Did archaeologists actually find the Persian metropolis walls?

The get-go one to denote that she had found part of the Persian city wall was the English language archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon. She carried out excavations in Jerusalem from 1960 - 1967. Above the Gichon spring she dug a long trench from meridian to bottom in order to analyse all layers of home of the ancient city. At the bottom of the gradient she found the city walls from the Middle Statuary Age (18th century BC) and the Late Atomic number 26 Historic period (effectually 700 BC). At the peak of the gradient there was a large tower and a stretch of metropolis wall from the Tardily Hellenistic period, built by the Maccabees in the 2d century BC. The Late Iron Age and the Maccabean period were two prosperous periods in the history of the town, in which solid city walls were erected around the southeastern hill.

Further north on the hill Kenyon establish a smaller tower with part of a wall that according to her originated from the Persian era. An authentic assay of the finds I made shows, however, that the belfry and the wall engagement from the Tardily Hellenistic period and are role of the fortifications described above (for an extensive analysis see Steiner 2022).

The excavations of Kathleen Kenyon. In the foreground the wall that she dated to the Western farsi period with behind it the small-scale tower. (Courtesy Ancient Jerusalem Projection).

Although I came to the decision that Kenyon was wrong and that the wall and the tower did not date to the Persian period, it is quite possible that a Persian wall was one time built there, now hidden under the later Maccabean constructions. At the foot of the belfry and wall was a thick layer of stony debris containing Babylonian and Persian pottery. My interpretation (and that of others) was that there had been a building on meridian of the hill in those periods, of which the remains, together with the pottery, had been swept downwardly the slope when a fortification was congenital on that spot. If the original wall would have been built in the Late Hellenistic period, i would expect pottery from the Babylonian, Early and Tardily Persian and Early Hellenistic periods in that rubble. All the same, the droppings only contained pottery from the Babylonian and Early on Persian periods. This suggests that the rubble was swept downward before the Tardily Persian period began, and that a metropolis wall may accept been built at that place at that time. In the Late Hellenistic period that construction then was rebuilt or restored and the older wall was not visible anymore. I am aware that this is only indirect evidence.

Recently, the Israeli archaeologist Eilat Mazar conducted excavations on the acme of the loma, where she found the so-called `Palace of David' (Mazar 2009; see for a refutation of that interpretation Steiner 2009). The small-scale tower that Kenyon had uncovered appeared to be on the verge of plummet and was demolished and rebuilt by her team. That provided an opportunity to look underneath and behind the tower. The pottery she found there originated in the Persian period, which, according to her, proved that the tower itself was Persian in date and therefore office of the fortifications mentioned in Nehemiah iii.

This, still, is a methodological error. If Persian pottery was found underneath the tower, this means that the belfry itself was built afterward. That could be two years later, a hundred years later or a thousand years later. The Persian pottery underneath the tower only gives a terminus mail quem, a date after which something could accept happened. The tower may thus take been built in the Western farsi period or (much) later. The finds do not disprove my dating of the tower in the Maccabean era.

All in all, archaeological research has not plant any bodily Persian fortifications but at nigh indirect bear witness for their construction. This does not immediately make the story in Nehemiah iii untrue, but information technology cannot be substantiated either.

Jerusalem in the Farsi menses

Another point is the size and office of Jerusalem during the Persian period. Was it a walled town with a central temple, the seat of the governor, the centre of government, religion and economic system? Or was it an unimportant, undefended settlement, in which just the local temple even so had whatsoever meaning?

In 586 BC the Babylonians left behind a town largely destroyed. They appointed a governor over Judah, who sat in Mizpa, not Jerusalem. Judah and her capital were mostly in ruins, its population decimated, the economy destroyed. A book about Judah in the Babylonian era is aptly subtitled The Archaeology of Desolation (Faust 2022).

How desolate Jerusalem really was, is a matter of interpretation. Many paint a night situation, with but some 'people of the land' living in the collapsed houses and making sacrifices in the ruins of the temple. Later on - in Farsi times - the temple would take been provisionally restored and Jerusalem would take been a non-walled, largely empty settlement where some priests lived who maintained the temple services.

Israel Finkelstein (2008), for example, sees Jerusalem of Farsi and Early Hellenistic times equally a pocket-sized village without walls, with at most a few hundred inhabitants. He points out that Persian fabric was found only on the southeastern hill, the City of David, and not in other parts of the site that were inhabited in the Late Fe Age. Fortifying the town would certainly not take been tolerated past the Farsi government, and the story every bit told in the biblical book of Nehemiah would be a much subsequently construction.

According to Oded Lipschits (2009) Jerusalem was a temple city. The temple was restored, and the temple gave the town its raison d'être. But that did not make Jerusalem a big or prosperous town. The seat of the Persian province of Yehud would therefore not be in Jerusalem just in Ramat Rachel, where a palace from the Farsi era has been excavated (Lipschits et al. 2022).

An authentic assay of the material found during excavations shows, in my opinion, a more nuanced moving picture. Around the urban center several tombs carved into the rock take been found that evidence a continuity from the Belatedly Iron Age onwards. The nigh famous cemetery is that of Ketef Hinnom, in the southwest office of the nowadays-mean solar day city, where a number of tombs have been excavated, nigh of them robbed except one which was full of luxury material from the Late Iron Age, the Babylonian and the Persian periods (Barkay 1994). 1 of the burying chambers independent, for instance, a silverish Greek coin from the end of the 6th century BC, the Early Farsi flow.

Reconstruction of one of the Ketef Hinnom tombs. (Photograph Chamberi / CC BY-SA ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) )

Some other burial ground was located in the Mamilla area, west of the current Jaffa Gate (Reich 1994). Several tombs have been constitute here with finds from the Iron Age unto the Hellenistic flow. The Farsi material included a statuary mirror, silverish rings, an Egyptian jar made of faience and an Attic jug - all luxury items, probably imported. Such tombs belonged to wealthy families, who buried their dead in that location for centuries. This would point that rich families notwithstanding lived in or around Jerusalem in the Persian period.

An assay of the pottery from the Farsi period found during excavations in Jerusalem shows that at that place were several potteries that supplied the inhabitants with vessels, including Greek-fashion vases and thin-walled bowls, both luxury materials (Steiner 2022). People didn't only eat what the state nearby yielded; fish bones were found from bounding main bream and mullet from the Mediterranean Ocean and catfish from the river Jordan or Lake Tiberias (Lernau 2022). Seal impressions begetting the proper noun Yehud - the Persian province of Judah - show that the site was part of an economic network. Wine and olive oil were brought to the town in sealed jars (Lipschits 2009). Jerusalem was, certainly in the subsequently Persian period, more than a sparsely inhabited settlement or just a temple city without any economic or administrative significance.

Diana Edelman, who fabricated an in-depth study of Jerusalem in Persian times based on biblical texts, archaeological finds and information on the Persian empire, sees Jerusalem as a birah, a modest fortress used past the Persians (Edelman 2005). It was Rex Artaxerxes I who would have moved the capital of the province from Mitzpa to Jerusalem considering the later site was more strategically located and had a better water supply. This fortress housed the governor of Yehud together with a garrison of soldiers and their families, as well equally local service personnel and merchants. This would imply the structure of supply and service buildings, a palace for the governor and houses for the inhabitants. It also included the reconstruction of the temple and the restoration of the walls. New migrants were sent from the Western farsi Empire to Yehud to aggrandize the farm production necessary for the regular army, and a governor was appointed with bequeathed ties to the area (Nehemiah). These new settlers would consist of descendants of the original exiles, but also of non-Judeans, such as retired Persian soldiers.

Charles Carter (1999) also sees no problem for the Persian authorities in allowing Jerusalem to restore its fortifications. He places this projection in the context of strengthening the interests of the Persian empire vis a vis the growing threat from Greece and Arab republic of egypt. This made information technology necessary to reinforce western Palestine, especially the provinces of Yehud and Samaria and the littoral areas (Carter 1999, 293).

Conclusion

The decision must be that no Western farsi city walls have actually been institute. Some scholars, all the same, do not allow themselves to be discouraged by this and draw with confidence a map of Jerusalem based on the biblical texts. Others conclude from the archaeological finds (or rather, the famine thereof) that Jerusalem in Persian times was a very small settlement, not including the western hill, impoverished, unwalled, insignificant. The stories as recorded in Nehemiah 3 tin therefore not be correct and must date from a later catamenia.

I take an intermediate position. Although the Western farsi boondocks walls have not been found, there are indications that they may exist hidden nether the later Maccabean fortifications. Merely irrespective of whether those walls did or did not be, in my opinion Jerusalem was not as desolate as is sometimes assumed, both before and afterwards the inflow of Nehemiah. Although piddling has been establish of the town itself, some finds suggest the presence of wealthy inhabitants, such as the rich elite graves that accept been uncovered. The pottery shows that several potteries provided the inhabitants not merely with fibroid utilitarian earthenware merely also with vessels in Greek style and refined bowls. The many Yehud stamp impressions betoken inclusion in an economic network, the verbal nature of which withal eludes u.s.a.. The fish bones analysed come up from fish from the Mediterranean Sea and Lake Tiberias.

Whether Jerusalem was a birah, a Western farsi fortress, or a provincial capital peradventure fortified by or with the permission of the Persian authorities to safeguard their interests cannot be determined on the basis of current testify. But perhaps there is more than factuality in the picture the book of Nehemiah sketches than is sometimes suggested.

Literature

G. Barkay, Excavations at Ketef Hinnom in Jerusalem, in: In: H. Geva, (ed.), Ancient Jerusalem Revealed, Jerusalem 1994, 85-106.

C. E. Carter, The Emergence of Yehud in the Farsi Flow –A Social and Demographic Study (JSOT Supplement Serial 294), Sheffield 1999.

D. Edelman, The Origins of the 2d Temple: Persian Imperial Policy and the Rebuilding of Jerusalem, London 2005.

A. Faust, Judah in the Neo-Babylonian Period: The Archaeology of Desolation, Atlanta, Ga 2022.

I. Finkelstein, `Jerusalem in the Western farsi (and Early Hellenistic) Flow and the Wall of Nehemiah', Journal for the Study of the Quondam Attestation 32 (2008), 501-520.

H. Lernau, `Fish Bones', in East. Mazar (ed.), The Superlative of the City Of David Excavations 2005–2008; Final Reports Volume I, Area Grand, Jerusalem 2022, 525-538.

O. Lipschits, `Farsi Menstruum Finds from Jerusalem: Facts and Interpretations.' The Journal of Hebrew Scriptures nine (2009), 2-30.

O. Lipschits, Y. Gadot et al., `Palace and Village, Paradise and Oblivion: Unraveling the Riddles of Ramat Raḥel', Near Eastern Archæology 74 (2011), 1-49.

East. Mazar, The Palace of Male monarch David. Excavations at the Summit of the City of David. Preliminary Report of Seasons 2005-2007, Jerusalem and New York 2009.

R. Reich, `The Ancient Burial Footing in the Mamilla Neighborhood, Jerusalem', in H. Geva (ed.), Ancient Jerusalem Revealed, Jerusalem 1994, 111-118.

K. A. Ristau, Reconstructing Jerusalem: Western farsi Period Prophetic Perspectives, University Park, Pa, 2022.

M. L. Steiner, `The "Palace of David" Reconsidered in the Light of Earlier Excavations', op http://www.bibleinterp.com/articles/palace_2468.shtml (2009) .

M. L. Steiner, ` The Persian Period City Wall of Jerusalem ', in I. Finkelstein, I and N. Na`aman (eds.), The Burn Signals of Lachish; Studies in the Archaeology and History of Israel in the Late Statuary Historic period, Iron Historic period and Persian Period in Honor of David Ussishkin, Winona Lake, Ind. 2022, 307-17.

M. 50. Steiner, `One Hundred and Fifty Years of Excavating Jerusalem', in B. Wagemakers (ed.), Archaeology in the Land of `Tells and Ruins'. A History of Excavations in the Holy Land Inspired by the Photographs and Accounts of Leo Boer. Oxford 2022, 24-37.

Grand. L. Steiner, `The Metropolis of David as a Palimpsest', in L. Niesiołowski-Spanò and E. Pfoh (eds.), Biblical Narratives, Archaeology and Historicity: Essays In Honor of Thomas Fifty. Thompson, London 2022, iii-10.

D. Ussishkin,. 2006. `The Borders and de Facto Size of Jerusalem in the Persian Menstruation', in O. Lipschits and M. Oeming (eds.), Judah and Judeans in the Persian Menses, Winona Lake 2006, 147–166.

What Stones Were Used To Repair Broad Wall Nehemiah,

Source: https://bibleinterp.arizona.edu/articles/walls-nehemiah-built-town-jerusalem-persian-period

Posted by: martinezbither.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Stones Were Used To Repair Broad Wall Nehemiah"

Post a Comment